Happy Holidays from Linda Kohanov and the Epona Herd!

Special thanks to our Dutch apprentice and valued friend, Ineke Rietveld, for all the photos featured in this newsletter.

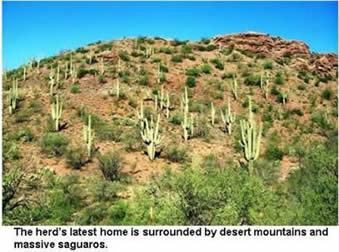

There’s snow on the Rincon Mountains here in Vail, AZ but the horses are staying warm with their furry coats and nightly dose of a warm bran mash doused with apple juice. Several neighbors somehow managed to decorate the huge saguaro cacti in their front yards with multi-colored lights, casting a surreal glow across this dramatic Sonoran desert valley just outside of Tucson.

As I write my new book by a crackling fire, I have much to be thankful for this year. Though we had to move from our beautiful home at Apache Springs Ranch this summer, reorganizing Epona’s operations to fit the realities of the current economy, many unexpected opportunities have emerged. The Merlin’s Spirit program for returning military personnel and their families continued this fall, with soldiers from the Ft. Huachuca army base attending one and two-day seminars. Thanks to all who donated to the Merlin’s Spirit fund! The soldiers, all recently returned from Iraq and Afghanistan, were deeply moved by their interactions with the horses.

As I write my new book by a crackling fire, I have much to be thankful for this year. Though we had to move from our beautiful home at Apache Springs Ranch this summer, reorganizing Epona’s operations to fit the realities of the current economy, many unexpected opportunities have emerged. The Merlin’s Spirit program for returning military personnel and their families continued this fall, with soldiers from the Ft. Huachuca army base attending one and two-day seminars. Thanks to all who donated to the Merlin’s Spirit fund! The soldiers, all recently returned from Iraq and Afghanistan, were deeply moved by their interactions with the horses.

Over the last six months, we have also made contact with regional Native American tribes, and have initiated the process of forming our own non-profit foundation to take this work to a variety of worthy populations. (The Merlin’s Spirit fund will be moved to the new EponaQuest Foundation soon— more to come as details solidify.)

Over the last six months, we have also made contact with regional Native American tribes, and have initiated the process of forming our own non-profit foundation to take this work to a variety of worthy populations. (The Merlin’s Spirit fund will be moved to the new EponaQuest Foundation soon— more to come as details solidify.)

And I’ve been continually inspired by members of our 13th Apprenticeship class, which we’ve been holding at Grand Adventures Ranch in Sonoita, AZ. This diverse international group of talented and dedicated people will be leading their final two-day workshops there in March, and from the work they’ve produced so far, I suspect they’ll all graduate with honors.

Back From Maternity Leave

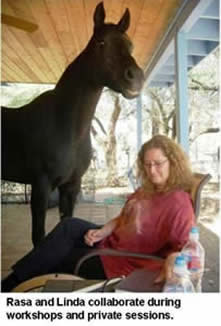

The small desert ranch I’m renting has not only proven to be a quiet and scenic writer’s retreat, it’s a great place to hold more intimate workshops. For the past four years, Rasa and Comet have been on maternity leave. Though visitors to Apache Springs enjoyed watching them live and mate with herd patriarch Midnight Merlin, give birth, wean and cavort with their ever expanding families, opportunities for actually working with the black horses were limited during that time. This fall, however, the herd moved back into facilitator mode, and I was amazed at how powerful they had become. Rasa stepped forward to lead some profound interactions. In one private session I’ll never forget, she stood over a client as I drummed, dictating nonverbally when I should start and stop, helping this person access a healing vision filled with transformational archetypes. Even after all we’ve been through together, I don’t think I would have believed a horse was capable of this if I hadn’t experienced it myself. It seems that Rasa’s two close calls with death last year have resulted in an uncanny connection with a deeper reality. It’s as if she’s living between the worlds, or perhaps more accurately accessing both worlds simultaneously, and I’m more grateful than ever to be working, playing and meditating with her daily.

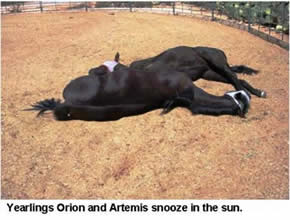

As the distinguished grandmother of the herd, Rasa pretty much has the run of the property several hours a day. Her three-year-old son Indigo Moon, his older brother Spirit, and Spirit’s mate Panther also enjoy nibbling grass in the backyard and knocking on the kitchen door for treats, as do Comet and Shadowfax. Comet’s son Orion and Spirit’s daughter Artemis, both yearlings, have been staring longingly over the fence, watching their parents work with a variety of people. At first I thought they were just pining for their herd mates. But when we’d return the older horses to their corrals after sessions, these youngsters would stand at the gate and paw, obviously hoping to lead a round pen session of their own. And so, occasionally, with more experienced clients, we give them a taste of facilitator life, and their surprisingly mature interactions have led to some inspiring insights.

As the distinguished grandmother of the herd, Rasa pretty much has the run of the property several hours a day. Her three-year-old son Indigo Moon, his older brother Spirit, and Spirit’s mate Panther also enjoy nibbling grass in the backyard and knocking on the kitchen door for treats, as do Comet and Shadowfax. Comet’s son Orion and Spirit’s daughter Artemis, both yearlings, have been staring longingly over the fence, watching their parents work with a variety of people. At first I thought they were just pining for their herd mates. But when we’d return the older horses to their corrals after sessions, these youngsters would stand at the gate and paw, obviously hoping to lead a round pen session of their own. And so, occasionally, with more experienced clients, we give them a taste of facilitator life, and their surprisingly mature interactions have led to some inspiring insights.

Workshops in 2010

As the deadline for my fourth book looms, I will be limiting my workshop schedule to one seminar a month, plus the apprenticeship (a new class starts in May), during the first half of 2010. I really enjoy doing these in-depth workshops for four to six people. It keeps the inspiration flowing as I write about the incredible insights the horses continue to impart through this work and through our daily reflections together. The Epona Center’s senior faculty, including Shelley Rosenberg, Carol Roush, and Mary-Louise Gould will be holding a number of introductory and advanced workshops as well, both in Southern Arizona and abroad. Check the website for their seminars and travels to Europe and Australia, and also look for Epona workshops with our wonderful Approved Instructors on five continents.

In the meantime, I still have one space available for the Tao of Equus mindfulness seminar in January. Another Black Horse Wisdom workshop is set for late February, again limited to four people. Back by popular demand is the Rasa Dance workshop for six people in April. Space is limited, so if you are interested in experiencing this work with the herd that urged me to undertake this astonishing journey to begin with, don’t hesitate to contact Carol Roush at booking@theeponacenter.com or 520-455-5058 for information and registration.

In the meantime, I still have one space available for the Tao of Equus mindfulness seminar in January. Another Black Horse Wisdom workshop is set for late February, again limited to four people. Back by popular demand is the Rasa Dance workshop for six people in April. Space is limited, so if you are interested in experiencing this work with the herd that urged me to undertake this astonishing journey to begin with, don’t hesitate to contact Carol Roush at booking@theeponacenter.com or 520-455-5058 for information and registration.

Wishing you all much joy and success in 2010!

A Taste of the New Book

As I continue to work on my new book exploring visionary leadership, emotional intelligence and social transformation through the way of the horse, I’ll share excerpts from the manuscript in upcoming editions of Epona News. (All material copyright 2009 by Linda Kohanov.)

Here are a few paragraphs from the first chapter: “The Horse in My Cathedral.”

Leaders must somehow balance individual and group needs within their companies and the culture at large. They must sacrifice personal comfort and short-term gratification, yet avoid burn out, in part by setting effective boundaries with fans, foes, and the relentless energy of inspiration itself. To develop a thick skin, as new managers are so often tempted to do, is to lose the sensitivity necessary to creativity, and the compassion essential to effective leadership. To keep your heart open is to experience a certain amount of pain on a daily basis. Learning how to manage the discomfort, without simply shutting down, is possible. But the personal breakthroughs involved border on transformations most often associated with religious or mystical experience.

Models for great leadership, in fact, read like recipes for sainthood. As Boyatsis and McKee observe in Resonant Leadership, such people “deliberately and consciously step out of destructive patterns to renew themselves physically, mentally, and emotionally. These leaders are able to manage constant crises and chronic stress without giving into exhaustion, fear, or anger. They do not respond blindly to threats with fearful, defensive acts. They turn situations around, finding opportunities in challenges and creative ways to overcome obstacles. They are able to motivate themselves and others by focusing on possibilities. They are optimistic, yet realistic. They are awake and aware, and they are passionate about their values and their goals. They create powerful, positive relationships that lead to an exciting organizational climate.” And they’re masters at helping colleagues and employees rise to similar levels of creativity, emotional intelligence and social awareness, simply for efficiency’s sake, if not for altruistic reasons.

As I’ve so often asked myself, my colleagues, my mentors, sometimes anyone within hearing range, “Where’s the handbook for that?”

In the early 1990s, an initially frustrating attempt at renewal gave me the insight and later the tools to address some of these age-old dilemmas. I had recently resigned from my position as program director of a Florida public radio station to move to Arizona with my new husband, recording artist Steve Roach. After five years wrangling a group of energetic, highly opinionated, artistically-motivated people, not only at the station itself, but in the numerous special events and music festivals I organized along the Gulf Coast, I was ready for a break. Working as a freelance writer, living in the desert with my own private composer creating new works of art in the next room, was a dream come true, fulfilling yet economically unpredictable for both of us. So it wasn’t long before I also accepted a position as morning announcer at the local classical station. No longer dealing with the headaches of managing such an operation, I was expecting to hide out in the studio, enjoying a daily dose of Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. The problem was, even though the station was technically a part of a major university’s communications department, there was precious little communication going on. And so, after experiencing the employee/employer dynamic from the leader’s viewpoint, I was suddenly thrust back into the labor pool to re-evaluate both perspectives from the trenches.

On the surface, the station played sophisticated, soothing sounds. Behind the scenes, however, the administration was unnecessarily secretive and manipulative, playing political games, most often at the expense of female employees who were rarely, if ever, promoted. As a nationally-recognized music critic and former program director myself, my reputation garnered a certain level of respect from the administration. But watching colleagues deal with a capricious, incongruent system tested my patience. Consoling these people inadvertently became part of my job as several of my most creative work-related friends would burst into the announcing studio in tears, telling me ever more disturbing tales of mal-treatment to the tempestuous accompaniment of Rachmaninoff, Wagner, and Ravel. As a lowly announcer myself, I was powerless to initiate organizational change, yet as an individual with a certain amount of leadership presence, I could occasionally turn the tide in my own favor. The ability to teach these skills to my fellow employees eluded me, however, mostly because I was unaware of key nonverbal elements influencing the most frustrating, as well as the most successful, of these pivotal interactions.

At the same time, I was perplexed by the famous musicians I encountered. Most people, radio station managers included, suppress emotion, hiding their true intentions behind bland smiles and passive aggressive maneuvers, only to blow up at inopportune moments under stress. Yet artists rewarded handsomely for expressing emotion were also leading highly dysfunctional lives. It seemed that suppression and expression were two sides of the same dysfunctional coin, and my faith in the sanity of our species was deteriorating—fast.

And so in my mid-30s, while my husband was off touring Europe with several other musicians, I impulsively bought a horse. My intention was to ride into the desert, to get as far away as possible from the human race on a regular basis. Yet this beautiful, willful mare refused to comply with my escape plan. Testing me every step of the way, she showed absolutely no respect for my hard-won reputation. It didn’t matter to her that a well-known music magazine flew me to Los Angeles to interview k.d. lang one week, then sent me to Japan a month later to write a cover story on Brian Eno. There was no way I could impress my mount with stories of how another publication was arranging dinners with classical violin virtuosos Isaac Stern and Anne-Sophie Mutter in between meetings with jazz great Wynton Marsalis and rock guitarist Carlos Santana. She didn’t even care that I talked to Johnny Cash an hour before I drove out to the barn one day. Chatting with a country music legend did not make me a passable rider. All those years sitting at a desk, writing, listening to music, and talking into a microphone had cut me off from the fluidity, assertiveness, and balance-in-motion that even the most generous horse demands, and this mare was hell-bent on showing me exactly how my “prestigious” career made me weak and ineffective.

Yet a strange thing began to happen. As I became more adept at motivating my horse, focusing her attention, and gaining her respect, relationships at home and work improved. People commented on the change, yet no one could pinpoint what had shifted. I also noticed nonverbal dynamics at play in myself and others that were reinforcing dysfunctional patterns on both sides of the employer/employee relationship, though at first, I had no idea how to change the situation. It was like someone had suddenly turned a spotlight on interactions we’d been trying to maneuver in the shadows, and yet for years I was unable to even describe these observations to others. Over time, I realized that no matter how eloquently we humans advocated for change, how diligently we debated the issues, how zealously we strategized, what we couldn’t talk about was a much more powerful motivator of behavior than anything we could discuss. Working with horses quickly became much more than a diversion. It was the missing link in my education, as a writer, musician, wife, friend, employee, and, increasingly, as a leader.

Psychologists have observed that only ten percent of human communication is verbal. And yet in our culture, we’ve virtually become mesmerized by words as our social and educational systems teach us to dissociate from the body, the environment, and the subtle nuances of nonverbal communication. Increasingly these conversations don’t even take place in person as cell phones, email, and text messaging proliferate. Where in the world do we go to master that other 90 percent? For me, the most rustic of boarding stables proved a worthy setting. In fact, there was no end to the character-building exercises my growing herd saw fit to impose. Through a relentless series of experiential lessons, my four-legged companions transformed me into a more engaged, assertive, intuitive, adaptable, and courageous person, not so much tutoring as tuning me, helping me over time to hold a more balanced frequency. I was amazed to find that, like Pegasus, the mythical winged stallion who inspired poets, artists and musicians, my horses could dispel the worst case of writer’s block through the simplest interactions. Like Zen masters, these exquisitely mindful creatures helped me navigate paradox with increasing facility. They even held the key to dealing with emotion effectively, and it didn’t involve suppression or expression. I could act horse-like in all kinds of perplexing human situations and completely change the outcome for the better. The barn took on a mystical patina as my equine friends taught me more in silence than anyone ever had in words.

It’s taken me a good 15 years to translate horse wisdom into spoken and written language, and yes, I can even inject significant logic into the discussion. Much of the research allowing me to do this didn’t exist when I started this journey in 1993, so it seems I was born at the right time and place to take on such a project. Over the years, through much experimentation, I also developed ways of teaching these same skills to others. While there is much I can now offer in conference rooms and lecture halls, my horses remain the true masters at transforming human behavior, illuminating ineffective habits and hidden strengths, teaching awareness and eventually mastery of that “other 90 percent” with remarkable ease and efficiency.

In this respect, it’s absolutely no accident that the most effective historical leaders—from Alexander the Great to George Washington to Ronald Reagan—were skillful horsemen, equestrians who had close relationships with spirited, arguably heroic horses. Regardless of policy and agenda, these men exhibited exceptional poise under pressure, clarity of intention, courage, and conviction. Their mounts were not mindless machines. They required — and continued to foster — an almost supernatural level of leadership presence capable of motivating others to face incredible odds and create innovative, highly ambitious empires. That Alexander the Great and George Washington rode the same horses into battle year after year also demonstrates the ability to cultivate relationship as a source of power: to tap resources without taxing them, even under the most dangerous and desperate circumstances. Their horses returned the favor, saving their lives on more than one occasion.

Business, politics, education, and religion may seem like opposing forces at times, but they all share one significant, potentially fatal flaw: mistrust of the body. As such, civilization has interrupted the optimal flow of human evolution. Your body is the horse that your mind rides around on. It’s a sentient being, not a machine. Starve that horse, beat it into submission, ignore its vast stores of nonverbal wisdom, and it will fail you when you need it most, throwing you during a crisis, perhaps wandering into traffic at the most inopportune moment. Reawakening corporeal intelligence, learning to form a partnership with instinct, intuition, and emotion, these skills are essential in harnessing the strength, creativity, spirit, compassion, and endurance needed to manifest lasting, meaningful change.

There’s a whole herd of horses in my cathedral, and they remain my greatest teachers. This is the course, the handbook they’ve dictated in so many subtle and powerful gestures.