The following article and book excerpt by Linda Kohanov offers insights into how we can more effectively handle challenging situations and people. Linda will be leading two workshops highlighting these innovative skills in Ohio at the end of June.

The South African cleric and human rights activist Desmond Tutu once observed that “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” But what’s the average person to do? At home, school, work, and most definitely in politics, we all too often find ourselves standing by, watching volatile verbal altercations that sometimes erupt in shootings, beatings, and large-scale acts of terrorism. It’s not enough to ask, “Why can’t we all just get along?” We must make some serious culture-wide efforts to ask, “How can we all get along?”

Significant social change cannot take hold until sensitive, caring people become empowered rather than overwhelmed. We need thoughtful, compassionate individuals to enter situations where suffering and conflict occur, and show a different form of strength, one that holds people accountable without becoming abusive. Otherwise we will continue to see frustrated, disillusioned teenagers acting out violently, bullies stirring up fear to gain control, sociopaths callously thriving at others’ expense—and significantly larger numbers of bystanders dealing with feelings of helplessness and moral injury.

When tempers rise, taking productive action is difficult. But research shows that not acting can also be traumatic. In response to volatile personal, regional and world events, people can feel a sense of moral injury, which the Moral Injury Project defines as “damage done to one’s conscience or moral compass when one perpetrates, witnesses, or fails to prevent acts that transgress one’s own moral beliefs, values, or ethical codes of conduct.” The pain can be particularly debilitating for highly sensitive, intensely empathetic people. But there is a strength-building option for those of us who care deeply about what’s happening in our world and want to make a difference. In essence, it involves developing a nonpredatory approach to power, one that encourages people to keep their hearts open while taking thoughtful nonviolent action in response to fearful or aggressive people and animals.

This skill set can be exercised progressively—in much the same way that we methodically build up our muscles to gain increasing levels of physical fitness. However, the perspective involved is counterintuitive for people who’ve grown up in an intensely competitive, opportunistic, conquest-oriented culture like our own. The main challenge requires the ability to show up for a challenge and neither retreat nor fight back, neither reject nor yield to an aggressor, while using specific verbal and nonverbal cues to help de-fuse rising tempers before they blaze out of control.

Because our culture overemphasizes predatory metaphors for power, many people do not realize that another, life-enhancing, socially intelligent form of power exists. In fact, I don’t think I would have ever stumbled upon this skill set in a purely human context. I developed this mindful, empathetic, nonpredatory approach through working with a particularly troubled horse.

Merlin’s Gift

Twenty years ago, an abused stallion began a decade-long process of teaching me how to stand up to challenging individuals and help them channel their potential for the good of the herd and tribe. Midnight Merlin had been abandoned at a Tucson boarding stable because of his violent, unpredictable behavior. I naively thought that I could “heal” him with kindness, sympathy and understanding. But after he threatened to kill me several times, I realized that he needed much more from me: He needed me to embody a thoughtful, centered form of power infused with compassion, courage and self-control.

In the process, I learned how to translate many of these skills to working with aggressive and fearful human beings. I began to teach these skills to parents, teachers, social and political activists, law enforcement personnel, and mental health professionals worldwide through a series of workshops called The Power Behind Nonviolence.

This summer, my schedule allows me to teach only one such workshop, which will take place near Dayton, Ohio June 28 through 30. People can attend a one-day introductory skill building workshop on the 28th. Those who want to go deeper can practice some additional skills during two days of horse-facilitated learning activities (with much gentler horses than Merlin) on the 29th and 30th. No horse experience or previous interest in horses is necessary. For info and registration, see https://eponaquest.com/workshop/the-power-behind-nonviolence-horse-sense-for-challenging-times/

The following article, adapted from my fourth book The Power of the Herd, offers an overview of the historical and practical elements involved in developing the emotional heroism, nonpredatory power, and nonverbal communication skills that allow people to turn potentially violent situations into trust building opportunities for positive change. In this excerpt, I illustrate how several innovative historical figures, including George Washington and the Buddha, learned a similar skill set, in part through their little-known status as exceptional horse trainers.

From Chapters 9 and 10

Ancient Wisdom

Hooves laced with steel seemed to come at me from all directions as a coal-black stallion named Midnight Merlin ripped the lead rope out of my hands, bucked, whirled around, and lunged at me, rearing, striking, raging at a ghost. All I could do was hold my ground and pray that I was fierce enough to win his trust.

“I don’t want to be this strong person,” I kept saying over and over to myself, fighting the urge to run screaming out the arena as he attacked me, once again, for no apparent reason. To contain this violence, I would need to tap a form of power I wasn’t even sure existed. But first I had to get over my resistance to the by-then blatant fact that gentleness, sympathy, and understanding alone couldn’t begin to heal this savage wounded force.

Not only did I survive the ordeal, I was transformed by it. And in doing research for my fourth book over a decade later, I realized that gaining the trust of an angry stallion was an ancient power story, one that predicted greatness. But what did it mean? What skills and intrinsic personal qualities did this archetype promote?

Alexander and Siddhartha

At age ten, Alexander the Great proved to be the only person in his father’s entourage capable of riding an unruly horse named Bucephalus. As the Greek historian Plutarch tells it, no one could mount the black stallion, and even the grooms were afraid to lead him. Alexander alone noticed that Bucephalus was spooking at his own shadow. The young Macedonian prince took hold of the bridle and turned the quivering, snorting stallion into the sun. The boy spoke softly, stroking the horse for a while. Then, at the right moment, Alexander leaped onto the stallion’s sturdy back and took off at a gallop, reveling in the horse’s phenomenal vitality rather than trying to rein it in. The team went on to conquer the known world together.

At age ten, Alexander the Great proved to be the only person in his father’s entourage capable of riding an unruly horse named Bucephalus. As the Greek historian Plutarch tells it, no one could mount the black stallion, and even the grooms were afraid to lead him. Alexander alone noticed that Bucephalus was spooking at his own shadow. The young Macedonian prince took hold of the bridle and turned the quivering, snorting stallion into the sun. The boy spoke softly, stroking the horse for a while. Then, at the right moment, Alexander leaped onto the stallion’s sturdy back and took off at a gallop, reveling in the horse’s phenomenal vitality rather than trying to rein it in. The team went on to conquer the known world together.

Similar horse taming tales are told about a young prince who lived in northeast India over two-hundred years earlier, though his brand of power turned out to be much different than Alexander’s. Gautama Siddhartha, later known as the Buddha, was also raised to become an emperor-warrior, though he became a different kind of leader, one who emphasized compassion, mindfulness, and enlightenment.

There are literally thousands of legends that rose up around the Buddha in the centuries following his death at age eighty. One feature of his biography that persists in the more reliable as well as the more fanciful sources involves reports of outstanding horse training abilities. Accounts describe him as a cool and daring horseman who was nonetheless known for his unusual kindness to animals.

There are literally thousands of legends that rose up around the Buddha in the centuries following his death at age eighty. One feature of his biography that persists in the more reliable as well as the more fanciful sources involves reports of outstanding horse training abilities. Accounts describe him as a cool and daring horseman who was nonetheless known for his unusual kindness to animals.

During one classic story, Siddhartha tamed a wild stallion to impress Yasodhara, daughter of a neighboring king, and win her hand in marriage. One by one, suitors tried to mount the horse as terrified grooms restrained the enraged animal with ropes.

Like Alexander, the Indian prince took a more thoughtful, compassionate approach, calmly walking to the agitated animal, speaking softly, and eventually stroking his face and sides. When the stallion began to lick Siddhartha’s hand, a tentative sign of trust, the young man quietly eased onto the animal’s back, winning the contest. And Yasodhara became a royal horse whisperer’s wife.

The Invisible

Throughout history, these remarkably similar stallion-taming tales have been interpreted as evidence that Siddhartha and Alexander possessed miraculous talents. When faced with the task of rehabilitating an enraged stallion over two thousand years later, however, I realized that these men had developed a host of somatic emotional and social intelligence skills that great equestrians acquire quite naturally—yet find exceedingly difficult to translate into words. In the nineteenth century, such men were referred to as “horse whisperers,” a term still implying secret abilities that set gifted trainers apart from mere mortals. Yet as I discovered in working with Merlin, the seemingly more mysterious abilities involved are nonverbal and unphotographable, not supernatural.

Throughout history, these remarkably similar stallion-taming tales have been interpreted as evidence that Siddhartha and Alexander possessed miraculous talents. When faced with the task of rehabilitating an enraged stallion over two thousand years later, however, I realized that these men had developed a host of somatic emotional and social intelligence skills that great equestrians acquire quite naturally—yet find exceedingly difficult to translate into words. In the nineteenth century, such men were referred to as “horse whisperers,” a term still implying secret abilities that set gifted trainers apart from mere mortals. Yet as I discovered in working with Merlin, the seemingly more mysterious abilities involved are nonverbal and unphotographable, not supernatural.

Though not even vaguely as masterful as Alexander and Siddhartha, I emerged from my own “stallion taming” ordeal blessed with the awareness of many things previously unspoken, initially indescribable experiences that changed my understanding of power, qualities I developed subconsciously, then struggled for years to communicate through the written word.

In acquiring the most basic skills necessary to work with a violent, unruly horse, I also began to understand how exceptional horsemen were able to harness the talents and loyalty of large groups of potentially violent, unruly people. I realized it was no accident that a surprisingly high number of history’s most influential leader-innovators were accomplished riders, including Genghis Khan, Joan of Arc, George Washington, Katherine the Great, Andrew Jackson, Elizabeth I, Teddy Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill, among many others. Regardless of policy and agenda, these people exhibited significant poise under pressure, clarity of intention, courage, conviction, and charisma, motivating horses and people alike to transcend basic survival instincts and endure significant discomfort or uncertainty, sometimes inspiring entire populations to face incredible odds in service to ambitious (though not always altruistic) goals.

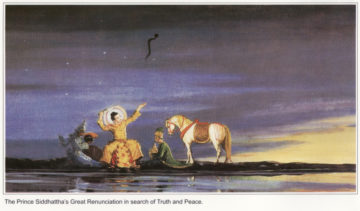

Alexander capitalized on these skills to expand his kingdom beyond all sense of decency, riding Bucephalus to previously unheard of success in war and conquest. Siddhartha, on the other hand, further developed his equine-inspired talents to pursue peace and enlightenment. Buddhist histories specify that it was another powerful horse, Kanthaka, who carried Siddhartha away from his father’s palace under cover of darkness, through the countryside and across the Anonma River where the adventurous prince embarked on the ultimate journey of freedom — from suffering, craving, hate, and delusion.

Some ancient texts insist Kanthaka died of grief when Siddhartha struck out on his own that night. But the horse was subsequently reincarnated as a brahmin (a member of India’s priestly caste) who, after attending talks by a then much older Buddha, easily took the teachings to heart, becoming enlightened himself—in his first human incarnation, no less!

Some ancient texts insist Kanthaka died of grief when Siddhartha struck out on his own that night. But the horse was subsequently reincarnated as a brahmin (a member of India’s priestly caste) who, after attending talks by a then much older Buddha, easily took the teachings to heart, becoming enlightened himself—in his first human incarnation, no less!

This evocative tale struck a chord in me when I encountered it two years after Merlin died. During the decade we spent together, the stallion had worked his own brand of magic on me, helping me gain a profound combination of mindfulness, fierceness, compassion, and self-control I can’t imagine accessing under any other circumstance. In the process, he became gentler, more thoughtful and increasingly trustworthy. Our experiences had clearly changed both of our lives for the better, prompting me to consider the deeper meaning behind the mythic relationship between Siddhartha and Kanthaka.

Yin and Yang

Horses embody many of the attitudes people access through more formal meditation techniques, including the ability to engage fully with reality. What seems so difficult for a grasping, hoarding, controlling, and competitive human being comes easily to these highly social, intensely aware, nomadic herbivores. Horses are actually hardwired for the state of nonattachment championed by the Buddha. In the wild, they don’t defend territory. They move unprotected with the rhythms of nature, cavorting through the snow, kicking up their heels on cool spring mornings, grazing peacefully in fields of flowing grass, despite a keen and constant awareness of predators lurking in the distance.

While they react quickly in the face of danger, they also show remarkable resilience in recovering from traumatic events. Yet unlike rabbits and other small vegetarians, adult horses are dangerous prey, using the power of the herd to successfully protect vulnerable members from wolves and lions. Still more impressive, horses have fought in the absolute bloodiest of human wars, sometimes receiving medals for exceptional bravery.

We often think of the relationship between predator and prey as synonymous with victim/perpetrator. Horses, however, embody a different approach to power, modeling the strengths of nonpredatory behavior: relationship over territory, process over goal, responsiveness over strategy, cooperation over competition, emotion and intuition over reason. And yet, they can be focused and assertive when the situation calls for it. They quite literally follow the ancient Taoist recommendation to “Know the yang, but keep to the yin,” which often appears in translation as “know the masculine, but keep to the feminine.” The Chinese sage Lao-tzu made this recommendation in the Tao Te Ching over 2,500 years ago, yet conquest-oriented civilizations emphasized the opposite. When a culture, like ours, keeps to the yang, discounting and degrading the yin, our ability to harmonize with other people, let alone nature itself, is seriously compromised.

At the same time, horses have little tolerance for timid, retiring, passive-aggressive people. If you sweetly ask for respect without the conviction to hold your ground, they’ll herd you around for sport, and become increasingly dominant, even dangerous, over time. Horses demand a balance of strength and sensitivity. If you have too much predator in you, they’ll shift toward evasion. If you don’t engage enough assertiveness, they’ll treat you like a plaything.

To transform a violent stallion like Merlin into a worthy partner, however, you also need to access an unusually courageous, socially intelligent form of leadership I’ve come to call emotional heroism.

The Silence of Power

Few men exemplified the benefits of emotional heroism as graphically as George Washington, a man who kept his sensitivity in tact on the battlefield, tempering great passion, ambition, and fierceness with personal restraint, adaptability, equanimity, and empathy, qualities he exercised daily on horseback.

Few men exemplified the benefits of emotional heroism as graphically as George Washington, a man who kept his sensitivity in tact on the battlefield, tempering great passion, ambition, and fierceness with personal restraint, adaptability, equanimity, and empathy, qualities he exercised daily on horseback.

While brief, eyewitness accounts of his impressive riding skills were commonplace, historians have failed to recognize the importance of Washington’s distinction as one of the finest horse trainers on either side of the Atlantic. He personally started most of his young mounts, and rode two exceptionally poised and loyal horses into battle throughout the Revolutionary War, retiring them in style at Mount Vernon (where they were visited by foreign dignitaries).

Thomas Jefferson later complained (when he and Washington became political rivals) that the persistent image of the elder statesman on horseback always seemed to trump the most eloquent speeches and persuasive intellectual arguments anyone else devised in opposition. Without saying a word, Washington radiated dignity, compassion, and power.

On the battlefield, Washington’s true genius was also expressed nonverbally. In the winter of 1777, for instance, he inspired a ragged group of soldiers to not only stick around for the Second Battle of Trenton, but to actually win it. John Howland, a young private from Rhode Island, lived to tell the story. In an account published years after the event, he struggled to remember what the general said, but never forgot how it felt to borrow the man’s courage.

As the British and their fierce allies, the Hessians, marched on Trenton, New Jersey, Howland was one of a thousand exhausted, half-starved, half-clothed troops assigned to delay the enemy’s advance through a gutsy attack and retreat/ambush across Assunpink Creek. “The bridge was narrow,” he remembered, “and our platoons were, in passing it, crowded into a dense and solid mass, in the rear of which the enemy were making their best efforts.”

Yet in that moment of utter confusion and desperation, Howland touched a vision of power, gaining, in the crush of battle, a sense of steadiness, renewal, and awe: “The noble horse of General Washington stood with his breast pressed close against the end of the west rail of the bridge, and the firm, composed, and majestic countenance of the General inspired confidence and assurance in a moment so important and critical…. I pressed against the shoulder of the General’s horse and in contact with the boot of the General. The horse stood firm as the rider, and seemed to understand that he was not to quit his post and station.”

Clearly, the dedication and poise that Washington’s mount exhibited inspired the same in young Howland.

A Deeper Courage

No matter how seemingly justified the cause war unearths labyrinths of trauma. Unrelated conflicts and tragedies from the distant past can affect the trajectory of current events in unexpected ways as human behavior becomes a minefield of opportunistic reactions to ancient pain.

George Washington learned this the hard way during his first tour of duty in 1754 when one of his allies, the Native American leader Tanacharison, needlessly massacred a group of French soldiers, punishing them for a childhood trauma perpetrated on his family by an unrelated group of Frenchmen fifty years earlier. The incident started the French and Indian War. Two decades later during the Revolutionary War, Washington actively prevented his own troops from taking out their frustrations on British prisoners of war, who, in the minds of many colonists, clearly deserved to be tortured and slaughtered for all kinds of heinous acts.

Washington’s emotional heroism allowed him to respond firmly yet thoughtfully in the face of violence coming from both sides. He strongly believed that for the country to have any hope of healing, let alone evolving, all citizens had to resist the retaliation impulse that effectively turned victims into perpetrators. In orders regarding prisoners of war, Washington advised his army to “Treat them with humanity and let them have no reason to Complain of our Copying the brutal example of the British Army in the treatment of our unfortunate brethren.”

Washington’s Policy of Humanity gained respect from British mercenaries like the Hessians, some of whom became loyal supporters for the American cause as a result. In this colossal demonstration of control over the basest instincts of his enraged troops, Washington’s eloquence of action demonstrated what Abraham Lincoln later so eloquently described in words: “I destroy my enemies when I make them my friends.”

Black Horse Wisdom

Over two-hundred years later, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh observed that “When another person makes you suffer, it is because he suffers deeply in himself, and his suffering is spilling over. He does not need punishment; he needs help….Happiness and safety are not an individual matter. His happiness and safety are crucial for your happiness and safety.”

No one made this more apparent to me than Merlin. Misunderstanding and punishment created the monster he became. Merlin’s first trainer had taken the young stallion’s mischievous antics personally, beating him over minor infractions and ultimately tying his head between his legs in a darkened stall to make him bow down in shame—and no small amount of pain—a form of torture that short-circuited Merlin’s nervous system. I knew I would never be safe around this frantic horse until this trauma was transformed—not through naive “it’s not his fault” indulgence, but through a heroic use of power combined with mindfulness and compassion.

When I first met Midnight Merlin, I couldn’t even walk into his stall and put a halter on him without a serious fight. Whenever I actually succeeded in getting close enough to touch him, he would jerk back and rear as if he’d been shocked by a cattle prod. Merlin seemed to try, sincerely, to keep it together. Then suddenly, without warning, he’d trip off into a rage, whereupon he’d either lunge toward me, rearing and striking with teeth bared, or he’d pull away and run around so frantically he’d lose his balance and slide, sometimes ten or fifteen feet across the arena into the fence, scraping his hide, lying there for ten minutes covered with sweat, staring blankly as if he’d given up the ghost while his pulse was racing frantically. These tantrums were heart-breaking to witness, and absolutely horrific if you happened to be in there with him.

At the same time, touch was so offensive to Merlin that experienced equine massage therapists and acupuncturists couldn’t get near him. To avoid further injury and trauma for everyone involved, I gave into a period of what I can only characterize as heroic wu-wei because, for the first week or two, doing nothing with Merlin involved a high level of vigilance and some serious self-defense skills.

I decided to see how far away I needed to stand from Merlin in order for the horse to calm down. My goal was to move closer inch by inch, until I was finally touching him. Instead, I found that Merlin demanded I stand in the same place day after day, about five feet from his body. If I even leaned in, he would pin his ears and begin to show the first signs of flight or fight. So I simplified the goal even further, spending ten to thirty minutes each day standing with the stallion in his corral, holding a whip in a neutral position in case he decided to attack, which he was progressively less motivated to do.

In the process, I developed a relaxed yet heightened state of awareness — out of necessity. If I held my breath or tensed my body in any way, Merlin would do the same, which meant he would either move away or attack. In terms of his/my rising physiological arousal, however, it was actually difficult at times to tell “who started it.” Because Merlin’s demeanor could change so quickly, it didn’t matter who started it. I had to address the situation immediately or it would get out of hand.

And so I began to think and react, not in terms of who was afraid, angry, or agitated, but more along the lines of assessing when fear, anger, and/or agitation were present in the horse-human system. By noticing the slightest rise in my own blood pressure, heart rate or tension, then immediately adding breath and relaxation, while simultaneously holding my ground, I could calm Merlin at a distance of five feet, often without lifting the whip — if I noticed the shift in its earliest, most subtle form and took immediate action to calm my own body while simultaneously conveying strength and power.

Talk about the benefits of stallion-induced mindfulness training! It wasn’t just about noticing what was happening. It was about sensing, then quickly altering my own body’s response to escalating tension, while simultaneously paying attention to another being. Merlin needed someone who could help him modulate his own out-of-control, traumatized nervous system. And by learning to do this for him, I was mastering this ability in myself.

It subsequently became clear what many of the horse-taming tales throughout history were pointing to: the nonverbal, somatic genius of exceptional leaders to control fear and aggression in large animals, and consequently in large populations. Think of Washington’s horse standing through cannon and musket fire, inspiring hundreds of shoeless soldiers to do the same when every fiber of their being was shouting “Retreat!” Consider the already advanced physical/mental/emotional self-control Siddhartha would have needed to gentle the enraged stallion he faced in winning Yasodhara’s hand in marriage.

In working with horses, the Buddha literally had a leg up in developing important skills he drew upon to make that final leap toward enlightenment at age thirty-five, striving over the next forty-five years, to teach these life-enhancing principles to other people. His sometimes clear and logical, sometimes vague and mystical teachings pointed to a reality that could never fully be translated into words.

In working with horses, the Buddha literally had a leg up in developing important skills he drew upon to make that final leap toward enlightenment at age thirty-five, striving over the next forty-five years, to teach these life-enhancing principles to other people. His sometimes clear and logical, sometimes vague and mystical teachings pointed to a reality that could never fully be translated into words.

In accepting the challenge to gain Merlin’s trust, my own mind-body awareness was elevated beyond anything I knew was possible. As Merlin forced me to stretch beyond my conventional human perceptions, habits, and skills, he stretched. We evolved in concert with each other, shedding limiting fears and beliefs to believe in each other.

When I came across accounts of the Buddha and Kanthaka, it struck me that this story could easily represent the first recorded case of mutual evolution between a human and a horse. What if the stallion that Siddhartha so skillfully trained had also been training him, psychologically as well as physically carrying his master away from the heavily defended, insulated palace of a hierarchical, materialistic father? In the process, the legend specifies, Kanthaka himself moved beyond instinct, further developing his species’ natural gifts for non-attachment, expanded awareness, and non-predatory power, later becoming enlightened as a student of the fully-realized Buddha.

In working with Merlin, I developed a few valuable rehabilitation techniques and a deeper understanding of the horse-human connection. But acknowledging that we were simultaneously separate and not-separate was the most powerful and elegant black horse mystery of all.

The Buddha described this principle as “dependent co-arising.” Thich Nhat Hahn called it “Interbeing.” But Merlin gave me a dramatic, direct experience of it when I became humble and patient enough to stand with him, waiting not just for a training solution as it turned out, but for a transformation of consciousness I later realized we all needed in order to heal the trauma and violence of generations.

These ancient pockets of pain and suffering—resurrected daily in our homes, schools, workplaces, communities, and political arenas—result not only from a lack of empathy but a lack of power, particularly a lack of nonpredatory power and emotional heroism, revolutionary qualities that men like George Washington tapped, and modeled for us, centuries ago.

“Let your heart feel for the affliction, and distress of everyone,” he advised.

That is true courage. That is mature leadership.

That is evolution.

This article was adapted from Linda Kohanov’s book The Power of the Herd: A Nonpredatory Approach to Social Intelligence, Leadership and Innovation. All rights reserved.

For more information and to register for the June 28: One Day Introductory Overview of Key Skills or the June 28 to 30: Three Day Equine-Facilitated Intensive in Ohio — https://eponaquest.com/workshop/the-power-behind-nonviolence-horse-sense-for-challenging-times/.